Enzyme: an experimental serializer for modern .NET

There’s a lot of serializers on .NET market. Some of them have cross-platform support some of them not. There’s one thing that is a foundation of a good serializer: it must be fast. Recently, I spent some time on extracting a piece that was in some sense a serializer and finally has become one. After spending some time with IL emit and benchmarking it, I must say that I’m quite happy with the results.

Unfortunately, the code is not OSSed. At the end I’m writing why. Still, you can enjoy the reasoning and results, and think about applying it in your scenarios.

Span of T

The are a few good things about Span:

- Span can be safely allocated on the stack using stackalloc.

- For small amounts of memory it can be faster than allocating an array or obtaining something from a shared pool (it’s about moving stack pointer - it’s cheap).

- It can wrap unsafe buffers so that the end user code can use an unsafe memory in a safe manner.

There are some disadvantages though:

- It can be used only on the synchronous path (it’s stack, it’s not transferable between threads).

- It must be created by the caller - once a function returns it removes its frame from the stack so there’s no longer on the stack…

- The caller needs to guess the size of the memory that needs to be passed to the called function. This makes it good for libraries which can include some guestimations etc. but in my opinion makes a really bad end user experience. You don’t want to TrySerialize all the time.

What if

So if we wanted to use span we’d need to ensure that:

- Objects are small. I’m a fan of saying that anything that is bigger than 1kB is much more similar to file sending than to serialization.

- The caller is not responsible for stupid guestimations about how big the buffer needs to be.

- It can be used on the synchronous path. Fortunately, if you think about batching IO in someway, this can be easily done, as the batching part will be highly likely synchronous. Even if it returns Task or ValueTask it will be done after writing.

New signature for serializer

We are used to serializing to following outputs:

- Stream, for example protobuf-net. Even if you use MemoryStream or some kind of pooling this can slow you down terribly. The Stream seam is extremely slow and not performing well.

- byte[], for example ZeroFormatter. Byte arrays are good if you pool them properly. Still, if you want to write more, you’ll need either to reallocate the buffer or to return the tail somewhat.

All the approaches above share the same assumption. It’s the fact that the control is returned to the caller after serializing an object. The function ends and the serializer is done. Nothing more. What if we could make it a bit different? What if serializer was calling a method to store the serialized data? What if we called it a writer?

void Serialize<TValue>(ref TValue value, IWriter writer)

and the writer would look like:

public interface IWriter

{

void Write(Span<byte>);

}

Now it’s the serializer who’s calling the writer. This means that the serializer can allocate on the stack as much memory as needed (and the amount that is reasonable) and can call the writer once the serialization is done. Yes, it’s one more stack frame, but still, we can close the allocation and the serialization within the serializer. And that’s a bit gain.

What about big objects? What if we estimate the size wrongly? These questions are great, but require a separate blog post.

Having this idea in mind, why don’t we spin a few benchmarks?

Benchmarks

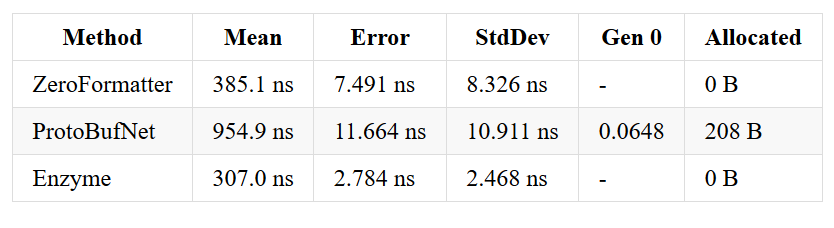

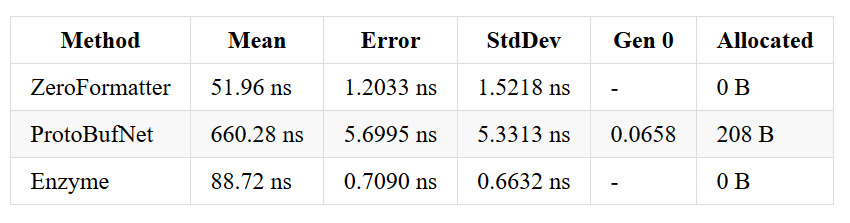

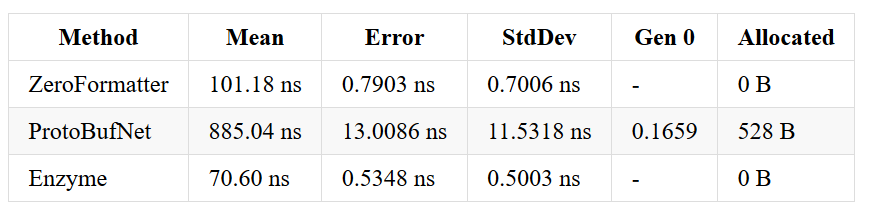

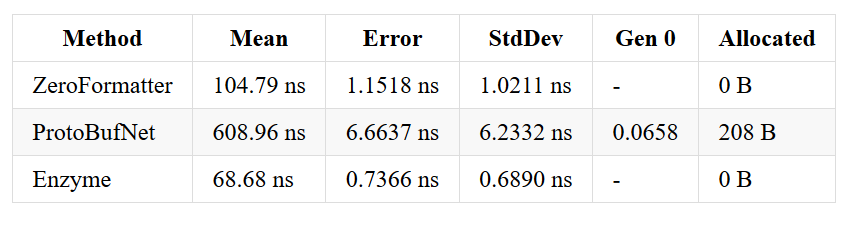

The benchmarks were run using the most awesome benchmarking tool for .NET BenchmarkDotNet. It consisted of several scenarios:

- An object with a single field/property with an array of strings:

"test1", "test2", "test3", "test4", "test5", "test6", "test7", "test8" - An object with a single field/property with an array of ints:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 - An object with a single field/property with an array of Guids:

8x empty Guid - An object containing three fields/properties:

bool,intandstring

Let’s take a look at runs where I compare Enzyme, protobuf-net and ZeroFormatter. Of course benchmarks lie and it’s comparing apple to oranges and all that stuff ;-)

Why ints are slower than ZeroFormatter? ZeroFormatter does not encode its values. Whenever you write an integer, it takes 4 bytes. Enzyme uses a zigzag encoding, similar to the one used by protocol buffers (and protobuf-net) which takes a bit more time but takes (for small numbers) only 1 byte per int. These bytes add up!

Why not OSS (yet)

I’m thinking about licensing it properly after reading entries from Marc Gravell and various tweets from Simon Cropp like this one. Both of them are great OSS .NET contributors providing enormous value to our ecosystem. Both struggle with big players (and small ones as well) requiring them to do something. I really need to learn a bit more about licensing before I release it.

Future

The future of Enzyme is open. Before making it OSS the licensing needs to be addressed. Also, I need to spend some more time on benchmarking and thinking about different cases. As I mentioned in the beginning, it was a part of something bigger and was tailored for specific purposes. Making it a general tool will take a bit more time.

I hope this article got you hungry and your digestive Enzymes are working. See you soon.

Comments

Zeroformatter seems a bit abandoned. It seems like neucc moved on to https://github.com/neuecc/MessagePack-CSharp.

Please consider comparing Enzyme to this project.

by Konrad at 2018-11-16 11:44:12 +0000Challenge accepted ;-)

by Szymon Kulec 'Scooletz' at 2018-11-19 16:25:38 +0000

Instead if OOSing it now, care to share what happens behind the scenes with basic code snippets?

by miguelcudaihl at 2018-10-02 00:14:23 +0000Will share some findings in the next post.

by Szymon Kulec 'Scooletz' at 2018-10-06 14:56:57 +0000I thought about serializers/formatters/parsers for quite a long time... I would love to see what you are cooking there.

1. When benchmarking serializers it is important to take into consideration:

a) byte/bit/"sub"-bit effective sizes. Building something like database engine.

b) serialization aaand deserialization speed, measured separately. Both might matter more in different contexts,

2. 4byte/byte/bit/sub-bit alignment strategies of storing(minimum bits/bytes) vs execution(4 bytes alignment is perfect for reads),

3. Handling of Type Discriminators (null, option, unions, enums),

4. "Fast" serializer/deserializer effectively means some option for static code generation per type/property/field,

5. Variable length types (taking just two bits from 32 bit value gives us 4 possibilities of encoding byte size for value).

6. Special handling of strings (character range is very low compared to how many bytes it effectively, usually takes).

7. Extra serialization options such as letting int property to be limited into having MaxValue of 12.

by Arek Bal at 2018-10-27 09:54:49 +0000I'm just getting back to reality after DotNetos conference. After a bit of recuperation I'll get back to this. Need to work on a few more bits and licensing (as the first commit constitutes the license).

You provided a really good list of things that need to be considered! 1b) Is one of the things that I'm working right now, as sometimes you don't need to deserialize the whole thing but only "visit" it reading some parts of it.

Anyway, thank you for this great comment. I hope I'll be able to share a bit (or byte ;-) ) soon

by Szymon Kulec 'Scooletz' at 2018-11-12 13:16:45 +0000