Red, Blue, and Purple

We all love async programming. Until we don’t. Just ask fellow engineers who were tasked with making a piece of code async. They might mention something about colors, like red or blue and hand wave some rules that one needs to follow. What the heck do they mean?

Red team vs blue team

The function coloring is a simple mental model one can use to deal with async-aware languages. Whether it’s C#, JS or TS, they all support the beautiful keywords of async and await. If you use their modern versions, you probably use them a lot. In this post we’ll focus on modern C# and what we can squeeze out of it. Let’s start with the following functions:

async Task<int> ProcessWithAzureAsync()

{

object payload = await SomeSlowAzureFunc();

int result = Process(payload);

return result;

}

int ProcessLocally()

{

object payload = Build();

int result = Process(payload);

return result;

}

int Process(object payload)

{

// Top secret implementation

return 42 + payload.GetHashCode();

}

Both methods, ProcessWithAzureAsync as well as ProcessLocally, perform almost the same operation. Eventually, they both call the Process. The main difference is how they obtain the payload required for further processing. The Azure version obtains it from a remote resource, therefore it uses the async-await to handle IO properly. The local version requires no such handling as it builds the payload locally, without calling third party remote dependencies. Let’s consider one more level of abstraction that would call one of the Process* methods.

int Combine()

{

int result = Process();

return result + _previous;

}

Can we substitute the Process call with any of the earlier introduced methods? We can do it with ProcessLocally for sure. What about ProcessWithAzure though? That would require changing the method Combine into:

Task<int> CombineAsync()

{

int result = await SomeSlowAzureFunc();

return result + _previous;

}

We can now see that asynchronous calls are bubbling up, making the caller incorporate the same asynchronous behavior. Nothing forbids us from calling the synchronous methods from the asynchronous though! If you’d like, we could sprinkle CombineAsync with some regular method calls.

Now, as red is usually considered to be more painful than blue, we could agree to color these functions accordingly. Let’s color asynchronous Task returning methods with red and all synchronous ones with blue. This would make ProcessWithAzure red but leave Process and ProcessLocally blue.

Having that said, let’s list all the rules that you need to follow:

- blue can call blue

- red can call blue

- red can call red

- blue can never call red

The 4th rule makes the whole thing a bit tragic (unless you flex with such things as sync-over-async). Once you leverage the asynchronous you MUST (in the RFC style) propagate it up. The caller of an asynchronous method must be asynchronous as well, etc.

The hidden state machine

When we look at the beautiful code that is asynchronous in its nature, sprinkled with async-await, there’s one thing that is hidden from us. It’s the async state machine. Why is it needed at all?

When you look at the asynchronous calls, their code can be split into two parts:

- Before the first await

- After the first await

The code that is after the await boundary might need to “wait” for the execution until the underlying asynchronous operation is finished. Now, you could ask should async-await not remove the wait? You are correct! It does it by introducing a notion of continuations and turning your method into a state machine that moves forward with each await. The continuation requires capturing its state and this is what the state machine does. Beside handling moving forward, it also captures everything that is required to perform such a move.

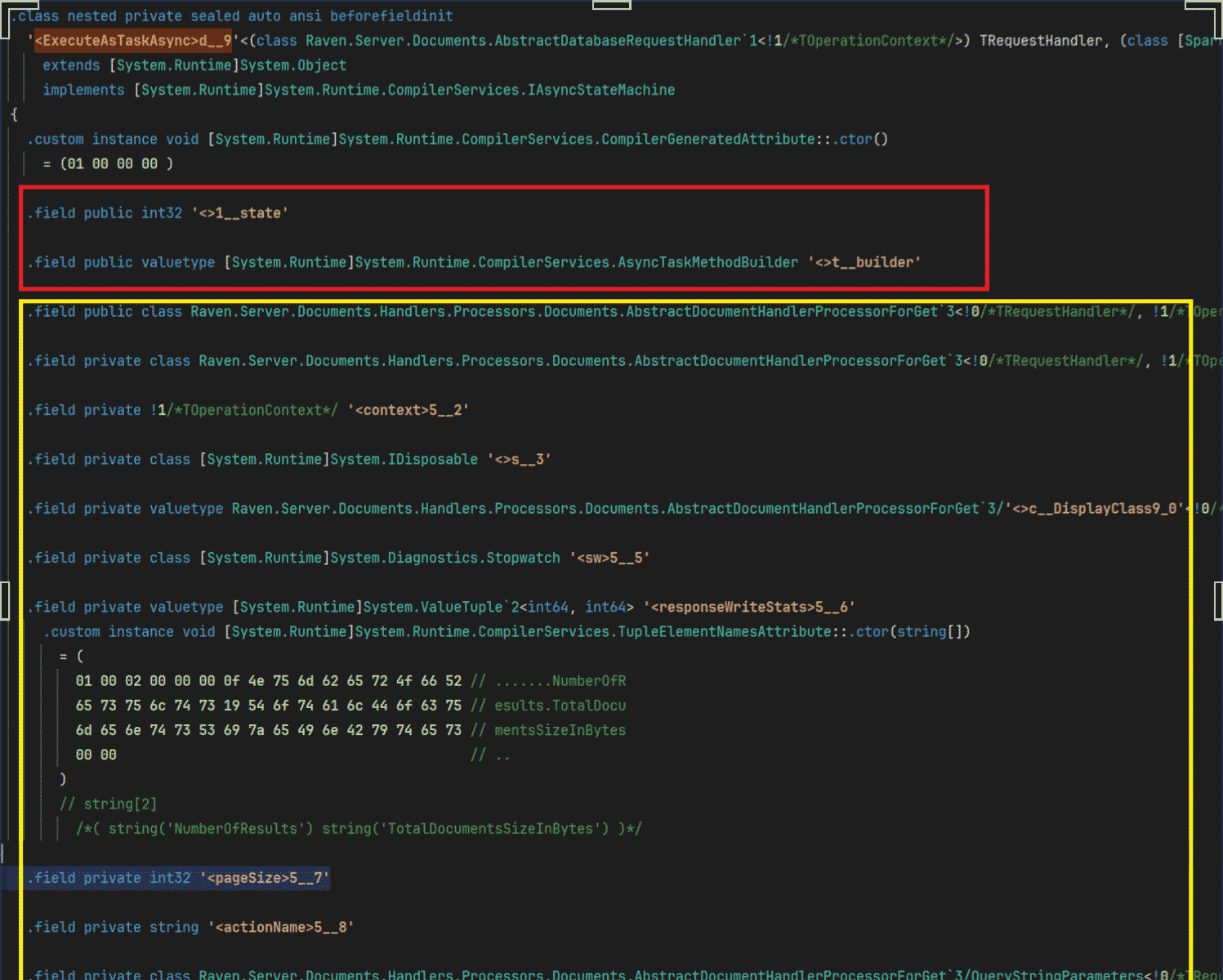

If this description got a bit complex, think how complex state machines can become to handle all these transitions! If the flow is heavily branched, they can be truly gargantuan. Let’s take a look at one of them. This example is extracted from RavenDB. You won’t see this in its C# code though, as it’s the C# compiler that emits this. The picture shows the underlying Intermediate Language (IL) that is later transformed into assembly.

We can see two fields marked with red. It’s the state of the state machine. There’s a lot of other fields here marked with yellow. These are all the poor variables that need to be captured between transitions. And the only way to have them captured is to allocate an instance of a class (shown above) and assign all of them. Again, usually this should be handled well, but in some cases, it might blow up. Now just count the fields. There’s a lot of them. Is there a way to optimize it away?

Elide like there’s no tomorrow

One way to do it is to follow the path of elision. Let’s consider the following two methods

async Task<int> ProcessWithAzure()

{

object payload = await SomeSlowAzureFunc();

int result = Process(payload);

return result;

}

async Task<int> ProcessWrapper()

{

return await ProcessWithAzure();

}

Let’s assume that for some reason we were required to wrap the actual ProcessWithAzure with an additional wrapper. Nothing else is done, beside a simple wrap. In this case, we could elide the call, meaning, remove the aspect of awaiting

async Task<int> ProcessWithAzure()

{

object payload = await SomeSlowAzureFunc();

int result = Process(payload);

return result;

}

Task<int> ProcessWrapper()

{

return ProcessWithAzure();

}

Although it can be done for simple cases, this can quickly explode when using a common syntax sugar handled for us by the C# compiler. Just consider this listing below.

async Task<int> ProcessWithAzure()

{

object payload = await SomeSlowAzureFunc();

int result = Process(payload);

return result;

}

async Task<int> ProcessWrapper()

{

using(var tx = BuildTransaction())

{

return await ProcessWithAzure();

}

}

You can’t easily eliminate the task here as the awaiting is scoped in the using clause.

So far we know that there’s the state machine, that we can elide some simple tasks. We have not discussed the construct called ValueTask that can be used to optimize it further. It’s about time!

Check out C# 9.0 Professional and learn the newest C# features!

The value of a ValueTask

The main idea behind the ValueTask can be summarized as the best possible common denominator for all the potentially (we’ll get to this in a second) asynchronous code. What are the cases then?

- Your method is async in nature (like the Task)

- Your method needs to follow a potentially asynchronous signature (ValueTask returning)

- Your method uses a low-level IValueTaskSource magic to allocate as little as possible and reuse the underlying objects.

There are caveats here, but thinking of ValueTask as a performance-friendly next step of asynchronous programming is the way to go. If you want to deep dive into it, please follow Task, Async Await, ValueTask, IValueTaskSource by Scooletz and Understanding the Whys, Whats, and Whens of ValueTask by Stephen Toub.

Purple is the new blue red purple

We know that we can follow blue (synchronous) and red (asynchronous) paths in our design. We already know that we can’t call the red from the blue. The question is whether there’s some middle ground between that could be leveraged for the performance focused code?

Let’s again consider the RavenDB codebase as an example. One of the features that were introduced a while ago, is a sharding capability. The sharding in the database landscape allows users to split the data between the nodes. Effectively, if your data size breaches the capability of one machine, you might consider it to scale up. We’re talking about terabytes of data and a swarm of requests. You can read more about it in RavenDB’s documentation. But what does it have to do with asynchronous programming?

Until the sharding was shipped, whenever a node was asked for a document, it was known that the data were kept locally. The node could query the local storage and, as the underlying mechanism for retrieving the data is based on the memory mapped files, just get them. With sharding, the situation is much different. If the database is:

- Non-sharded - data ARE retrieved locally.

- Sharded - data MIGHT require a jump over the network, to the node that keeps the given shard.

This takes the path that was previously blue (synchronous) and turns it into something that is sometimes red (asynchronous) but not always! Let’s call such a method blue + red = purple!

If I asked you to think about a method that sometimes executes in a synchronous way and sometimes not, there’s one example that probably would come to your mind. Hybrid caching! If the data is already stored in memory, we can return as is! If not, we need to fetch over the network to grab them. Let’s try to sketch such a snippet!

We know that the common denominator we will use is ValueTask. Let’s design a signature.

ValueTask<int> PotentiallyLocalCall()

Now comes the consumption part. What we want to do is to differentiate the happy fast path of synchronous execution. To do it, we’ll use a special property called IsCompletedSuccessfully

ValueTask<int> PotentiallyLocalCall() { ... }

ValueTask<int> ProcessWrapper()

{

ValueTask<int> result = PotentiallyLocalCall();

if (result.IsCompletedSuccessfully)

{

// synchronous fast path

}

// asynchronous slow path

}

To make the example truly purple we need to handle both paths now.

ValueTask<int> PotentiallyLocalCall() { ... }

ValueTask<int> ProcessWrapper()

{

ValueTask<int> vt = PotentiallyLocalCall();

if (vt.IsCompletedSuccessfully)

{

// BLUE path. Access the result directly

return new ValueTask<int>(vt.Result + 42); // 42 is magic, we need some

}

// RED path. Asynchronous slow path

return WrapAsync(vt);

}

static async ValueTask<int> WrapAsync(ValueTask<int> pending)

{

var result = await pending; // and more ...

}

Now we can tell that the function is truly purple!

- It calls something potentially asynchronous.

- It dispatches the synchronous path using direct access to the result.

- It leaves the heavy asynchronous for a separate method.

Not so easy!

The unfortunate part is that this flow can sometimes be complex! Especially, when you build a document database that needs to operate with potentially sharded data that might require requests to another node! In this case, finding the place where the async-await is capturing much too much might not be a trivial task (pun intended). And it was not.

The mentioned example included some scoping and two execution paths. By scoping, I mean the usage of using clauses. By two execution paths I mean an if that was in the middle.

async Task NotSoEasy()

{

using(scope)

using(scope2)

{

if(condition)

await call1();

else

await call2();

}

}

This made it not so easy to work with. The scope removal was done with a borrow-like data structure. Before the actual async call, it was just kind-of bumped up to not dispose of the scope. The calls were effectively refactored to assign the value to a ValueTask variable declared above. If we worked with the snippet provided above, it’d be transformed to something like below. Notice that the method is no longer async!

Task NotSoEasy()

{

using(var b = scope.AllowBorrow())

using(var b2 = scope2.AllowBorrow())

{

ValueTask vt = condition ? call1 () : call2();

if (vt.IsCompletedSuccessfully)

{

HandleResult(vt.Result);

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

// The slow async path! We failed to succeed in a sychronous call

return HandleAsync(b.Borrow(), b2.Borrow(), vt);

}

}

This wasn’t the easiest one! Just take a look at the actual PR .

Use it always, not!

As usual, this kind of performance hunting should be performed only when pointed at by benchmarks or profiling. With time one learns what is costly, and what is not, but the ultimate truth is always revealed by the actual hot paths in your code. And then, if you see a lot of red in there, and you see some potential for mixing in some blue ,you can paint them purple.